Oct 10, 2023 | RESEARCH

By John Slabczynski

See original article on The BASIS HERE.

Many countries, such as the United Kingdom (UK), have created powerful regulatory bodies which are meant to protect consumers and mitigate risks that come with gambling. These regulatory bodies are not perfect, however. They can be slow to adapt to changes in the gambling landscape such as the rise of online gambling. Further complicating these issues is the presence of cryptocurrency-based1 online gambling operators. While online gambling carries its own risks, crypto gambling might be especially risky for consumers due to the lack of regulatory oversight. Research on the association between crypto-trading and gambling problems also suggests that individuals who engage crypto-gambling may be especially at-risk for gambling problems. This week, The WAGER reviews a study by Maira Andrade and colleagues that reviewed the responsible gambling (RG) features offered by crypto-based online gambling operators.

What was the research question?

What kinds of RG features do cryptocurrency-based online casinos employ?

What did the researchers do?

The researchers collected data from 40 cryptocurrency-based online casinos that were accessible from the UK. Of these, 22 were accessible directly from within the UK, while 18 required a VPN connection to access. The researchers then searched for the presence of seven features intended to promote RG on each of these sites. These included: (1) thorough account registration requirements, (2) a dedicated RG page, (3) separation of promotional material from the RG page, (4) availability of RG tools, such as deposit limits, (5) accessibility of gambling history, (6) RG material promoted via email, and (7) having RG-oriented customer service. (The researchers coded other crypto-based features, but we are not reviewing them here.)

What did they find?

The majority of operators required only minimal information to register. Fourteen sites required an email address (or less), and none required proof of age. The presence of responsible gambling material was also limited; though 31 out of the 40 sites offered an RG page, many contained either promotional material, suggested that gambling was a way to make money, or were otherwise insufficient in educating consumers about gambling-related harms. Slightly over half of the sample (62.5%) provided at least one RG tool, though these were also often limited or not user friendly. Notably, however, 39 of the websites offered gamblers access to their gambling history. Email communication was especially problematic among these sites. Only five sent emails containing RG information, and an additional five either didn’t respond or sent potentially harmful information after a hypothetical request for help from a consumer2 (see Figure).

Figure: Number of crypto-based online casinos with each of the seven RG features.

*One operator was not rated because they did not require an email at registration.

**Two operators were not rated on this criteria.

Why do these findings matter?

These findings could help regulators, researchers, and policymakers understand the current landscape of crypto-based gambling. For example, it’s possible that youth might be engaging with these sites, leading to potential current and future gambling-harm. Other findings suggest that these operators’ RG practices often involve harmful or incorrect information regarding gambling safety, which might increase gambling-related harm instead of reducing or preventing it.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

The researchers did not make deposits or otherwise gamble on any of the crypto-based gambling sites, so they did not get the full customer experience. As such, it is possible that the researchers missed some of the sites’ features or that their records of the sites’ features contain inaccuracies. For example, though the study found that 39 sites offered access to an accounts gambling history, it is unknown whether these were accurate reports or how frequently they were updated. Additionally, despite reviewing 40 sites, this sample is relatively small compared to the overall number of crypto-based gambling sites.

For more information:

Individuals who are concerned about their gambling may find support through the National Council on Problem Gambling or with Gamblers Anonymous. Additional resources can be found at the BASIS Addiction Resources page.

—John Slabczynski

1. Cryptocurrency refers to a digital asset that is worth money and can be used to buy goods and services. The most popular and well-known type of cryptocurrency is Bitcoin, which was released publicly in 2009.

2. To examine potential responses to someone experiencing gambling problems, the researchers sent requests to all 40 websites with the following text: “I want to control my gambling. Can you give me any information on how I can do that? I feel a bit addicted and sometimes I can’t control the money I’m spending.”

Aug 15, 2023 | RESEARCH, YOUTH GAMBLING

By Kira Landauer, MPH

See original article on The BASIS HERE.

Gambling is a common activity among adolescents. Most adolescents gamble without consequences but some experience gambling-related problems and associated harms, including disrupted social relationships, academic challenges, delinquency, and criminal behavior. Their gambling behavior might be influenced by the gambling attitudes and behaviors of their family and friends. This week, The WAGER reviews a study by Megan Freund and colleagues that investigated whether exposure to other people’s gambling is associated with the gambling behavior of Australian secondary students.

What was the research question?

Is exposure to other people’s gambling associated with past-month gambling, types of gambling activities, and at-risk or problem gambling among a sample of Australian adolescents?

What did the researchers do?

Students (n = 6,377) from 93 secondary schools in the Australian states of Victoria and Queensland participated in the Australian Secondary Students’ Alcohol and Drug Survey. Participants reported whether they had ever gambled and their past-month gambling behaviors, including the types of gambling activities they engaged in (i.e., hard or soft1). Students who reported ever gambling were screened for problem gambling. Participants were also asked whether their parent/caregiver, brother/sister, best friend, or other relative had gambled in the past month. The researchers assessed the associations between other people’s gambling and students’ past-month gambling, types of gambling activities, and at-risk or problem gambling.

What did they find?

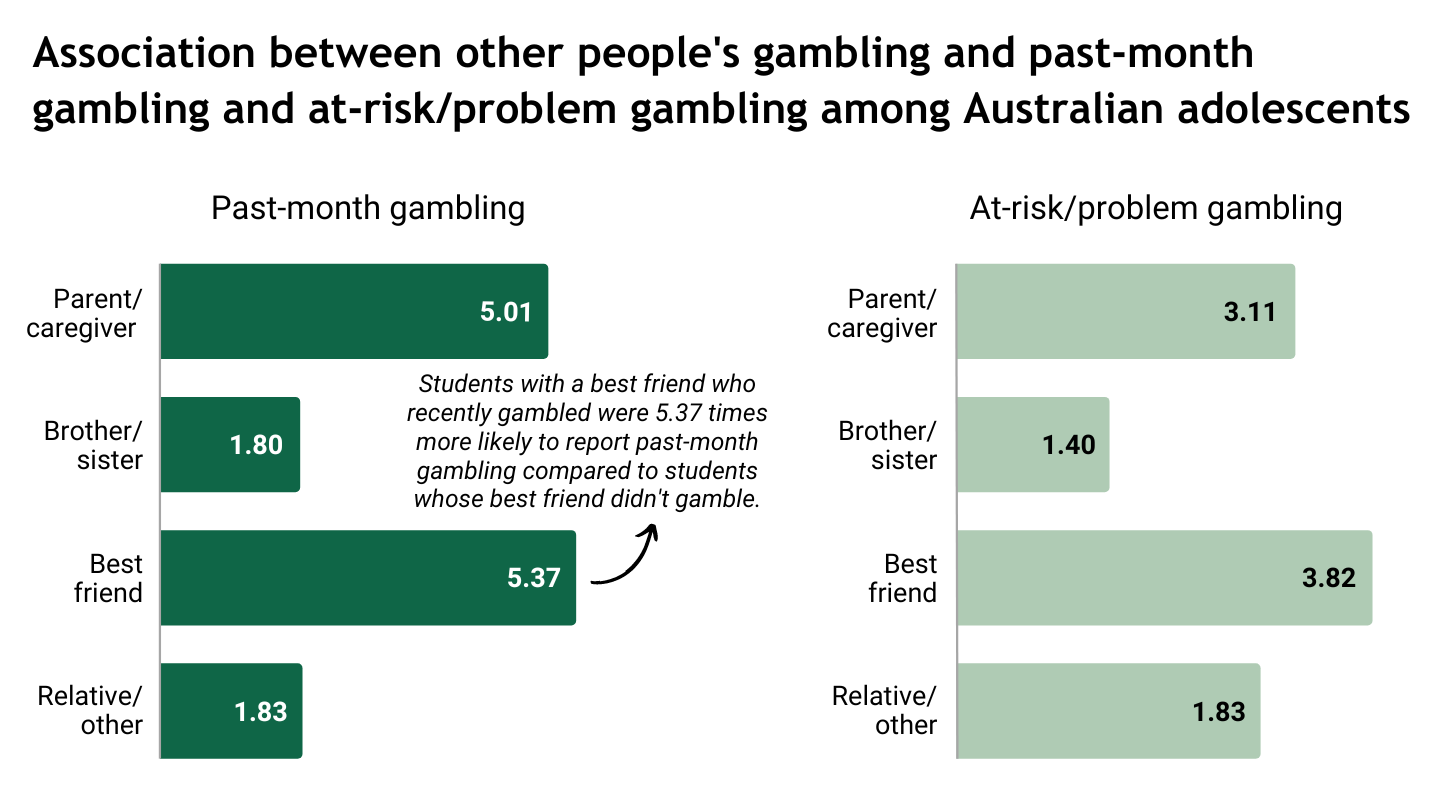

Thirty-one percent of students in the sample reported ever gambling and six percent had gambled in the past month. Ten percent of students who ever gambled were classified as either experiencing at-risk (8%) or problem gambling (2%). One in five students reported that someone in their household gambled in the past month. Most frequently, students reported past-month gambling among fathers (16%), followed by other relatives (14%). Students were more likely to have gambled in the past month, played any hard gambling activity, and be classified as an at-risk or problem gambler if they had a parent/caregiver, brother/sister, best friend, or other relative who had gambled in the past month. Past-month gambling and at-risk/problem gambling were most likely among students whose parent/caregiver or best friend had gambled (see Figure).

Figure. Odds ratios of the association between other people’s gambling (parent/caregiver, brother/sister, best friend, other relative/someone else) and past-month gambling and at-risk/problem gambling among a sample of Australian secondary students (n = 6,377).

Why do these findings matter?

These findings confirm the association between exposure to gambling in family and friends and gambling behaviors among adolescents. Young people with a parent/caregiver or close friend who gambled were most likely to have gambled recently, engaged in hard gambling activities, and to have experienced at-risk or problem gambling. These findings should inform future problem gambling prevention and education initiatives for young people, such as family-focused initiatives. Successful initiatives might also include skill development for young people, such as how to resist peer pressure to gamble.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations of this study?

Data were self-reported, so the results might be subject to recall bias and social desirability bias. Because the study was based on a sample of adolescents and was conducted in Australia, the findings might not be generalizable to people in other places with different gambling landscapes.

For more information:

Do you think you or someone you know has a gambling problem? Visit the National Council on Problem Gambling for screening tools and resources. For additional resources, including gambling and self-help tools, visit our Addiction Resources page.

— Kira Landauer, MPH

1. Hard gambling activities are generally defined as having higher stakes or a more rapid pace of play (e.g., poker, casino games, sports betting) compared to soft gambling activities (e.g., lottery tickets, scratch cards).

Aug 14, 2023 | RESEARCH

For the past three years, since the start of the pandemic, NCPG has offered virtual workshops prior to its regularly scheduled annual conference. This year NCPG presented a range of speakers and topics over the course of two afternoons. One advantage of online workshops is the ability to host international speakers, who might not ordinarily be able to travel. It’s also helpful for those who cannot travel to the NCPG annual conference, providing access to excellent resources from the comfort of their computers.

Several of the presenters were from the United Kingdom, where they have been dealing with the backlash from the 2005 policies that blew the door open on gambling accessibility and are now feverishly working to increase treatment services, prevention and research. Attendees benefited from listening to the lessons learned and hopefully can apply those lessons in their own backyards.

Several researchers presented on their most recent studies looking at the effectiveness of self-exclusion programs, the links between gambling and problem debt, the ever-evolving changes in gambling and responsible gambling language, and the value of providing peer support groups for women. We heard from clinicians and their experiences treating gambling as a co-occurring disorder and about a fairly new integrative treatment model called Congruence Couple Therapy (CCT), which has been shown to have a relative advantage over individual treatment for reducing addictive and mental health symptoms and improving emotional regulation among couples. There was also a panel discussion advocating for gambling policies to move into the national spotlight. With no federal funding, and the increased opportunities to gamble, the field of gambling disorder is behind in workforce development, research and programs regulating gambling harm.

See the full Summer 2023 Northern Light Newsletter (PDF).

Jun 27, 2023 | RESEARCH, SPORTS BETTING

Read the original article on The Basis HERE.

By John Slabczynski.

Video games have drawn the attention of activists and public health advocates since as early as the 1970’s. Many of these activists have focused on the intense depictions of violence in video games and suggest that these depictions may lead to real-life violence. One area that is often neglected, however, are depictions of substance use and gambling in video games. Although regulators have begun to investigate loot boxes and their relationship with problem gambling, other forms of gambling in video games have received less attention. For example, skin betting (i.e., exchanging virtual goods for digital gambling currency) — which was first popularized by the game Counter-Strike: Global Offensive — has evolved from betting on in-game matches to skins being used as currency in other games of chance such as roulette. Many of those involved in these underground gambling networks are adolescents who are unable to engage in traditional gambling. This week, the WAGER reviews a study by Nancy Greer and colleagues that examined links between esports, skin betting, and problem gambling.

What was the research question?

How does esports and skin betting relate to other forms of gambling and gambling harms?

What did the researchers do?

The researchers recruited participants through Amazon Mechanical Turk and social media posts in online gaming communities to participate in an online survey. All participants reported either esports cash or skin betting, or gambling skins on games of chance in the past 6 months. In total, 737 participants completed the survey. The survey itself focused on four broad categories: (1) video game involvement, (2) video game-related gambling (including betting on esports), (3) traditional gambling, and (4) problem gambling and gambling-related harms. The researchers used ordinal logistic regression to test the hypothesis that video game involvement increases the likelihood of engaging in video game-related gambling, which in turn increases the likelihood of engaging in traditional gambling and experiencing gambling harms.

What did they find?

Though video game involvement related to video game-related gambling, video game-related gambling was only slightly related to traditional gambling. Consider three different video game-related types of gambling: esports cash betting, esports skin betting, and skin betting on other games of chance. Of these, only esports cash betting frequency significantly predicted involvement in traditional gambling activities. Interestingly, although the sample overall reported high rates of problem gambling and gambling harms, neither esports cash betting nor esports skin betting significantly predicted problem gambling or gambling harms. When controlling for other forms of traditional gambling, only skin gambling on games of chance was predictive of problem gambling and gambling harms (see Figure).

Figure. This figure displays the odds of experiencing problem gambling and gambling harms based on video game-related gambling behaviors. Odds ratios above 1.00 indicate that for every one unit increase in the predictor variable (video game-related gambling behaviors) the odds of being one category higher in the outcome variable (problem gambling or gambling harms) increases by X times. An odds ratio below 1.00 indicates that the odds decrease by X times. For example, a one unit increase in esports cash betting frequency would mean a participant is 1.033 times as likely to experience a one unit increase in their problem gambling severity. Only skin betting on games of chance was significantly associated with either outcome variable.

Why do these findings matter?

These findings suggest that buying skins and esports gambling are not risk factors for problem gambling in and of themselves. Rather, skin gambling on games of chance appears to increase the risk of gambling harms. It remains unclear whether individuals who gamble skins on games of chance do so because they have exhausted other financial resources, or if skin gambling on games of chance directly increases the risk of problem gambling and other gambling harms. Regardless, these findings suggest that regulatory bodies should consider focusing on gambling operators who facilitate skin gambling on games of chance, rather than other more traditional esports focused operators.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

This study has significant limitations in terms of its generalizability. Participants were required to have gambled either on esports or via using skins in the past six months, so the results likely do not represent video game players as a whole. The study also failed to include anyone under the age of 18 despite the fact that many people who gamble using skins are adolescents. Additionally, due to the study’s limited sample size, the researchers were unable to conduct path analysis, an analytical technique that allows for estimating causal effects instead of only statistical associations.

For more information:

Individuals who are concerned about their gambling behaviors or simply want to know more about problem gambling may benefit from visiting the National Council on Problem Gambling. Others who want to learn more about video game addiction can find information via the Cleveland Clinic. Additional resources can be found at the BASIS Addiction Resources page.

May 16, 2023 | RESEARCH

Read the original article on The Basis HERE.

By Kira Landauer, MPH

Editor’s Note: Today’s review is part of our month-long Special Series on Asian American/Pacific Islander (AAPI) Addiction Research. Throughout May, The BASIS is examining forms of addiction among AAPI communities.

Emerging research indicates that the Asian American community is at greater risk for problem gambling than the general population. However, research often fails to include or accurately capture the realities of gambling and problem gambling within this community, particularly the experiences of Asian American working-class immigrant communities. This week, as part of our Special Series on Asian American/Pacific Islander Addiction Research, The WAGER reviews a study by Mia Han Colby and colleagues that investigated the systemic issues that contribute to gambling in the Greater Boston Asian American community.

What was the research question?

What are the systemic issues that contribute to gambling in the Asian American community of the Greater Boston area?

What did the researchers do?

The authors conducted forty semi-structured interviews with adult members of Asian1 immigrant communities in the Greater Boston area who had a family member, friend, neighbor, or coworker who gambled. Using a community-based participatory research approach, bilingual/bicultural community fieldworkers who had experience working in their respective communities interviewed participants. Participants were asked about their perceptions of gambling in their community, as well as impacts of gambling on families and the community more generally. The researchers analyzed the interviews for common themes pertaining to systemic issues related to gambling and problem gambling in the Asian community in the Greater Boston area.

What did they find?

The interviews revealed how the underlying issues of poverty and social and cultural loss due to immigration contribute to gambling in this community (see Figure). Many participants spoke about the challenges of making a decent living as an immigrant while working low-wage and stressful jobs. Gambling was viewed as a way to make money and improve a family’s financial situation. For example, one participant expressed that gambling gave them “hope that they can have freedom of money.” It was also seen as a way to relieve work-related stress.

Participants also spoke about the challenges of integrating into American society due to cultural and linguistic barriers. Many discussed the lack of appropriate and accessible social and recreational activities, which contributed to experiences of social isolation, loneliness, and boredom. Gambling—especially within casinos—was viewed as a means of socializing and connecting with other Asian community members. Many participants spoke about the ways that casinos targeted Asian clientele, including busing directly to casinos from Asian communities (e.g., from Boston’s Chinatown neighborhood), creating an Asian-friendly casino environment (e.g., employees speak Asian languages, concerts and events featuring Asian artists), and incentives (e.g., free food and discounts).

Figure. Reasons for gambling in Asian communities in the Greater Boston area, by percentage of respondents who identified each reason for gambling (n = 40).

Why do these findings matter?

These findings illustrate the complex and systemic issues that contribute to gambling in Asian communities in the United States, including social and cultural isolation due to challenges integrating into American society, and struggles working low-wage and stressful jobs. Asian CARES (Center for Addressing Research, Education, and Services) of Boston created actionable recommendations for change based on these findings. They recommend investing in neighborhoods where Asian immigrants live and work to create inclusive spaces that facilitate social and recreational activities other than gambling. Additionally, Asian CARES recommended increasing funding to trusted community-based organizations (e.g., Boston Chinatown Neighborhood Center) that provide culturally and linguistically responsive problem gambling, mental health, and social services (e.g., services that help individuals find and maintain employment).

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations of this study?

Data were self-reported and based on past experiences, so the results might be subject to recall bias. Findings from this study might not be generalizable to other geographic areas or to other immigrant populations.

For more information:

Do you think you or someone you know has a gambling problem? Visit the National Council on Problem Gambling for screening tools and resources. For individuals in Massachusetts looking for culturally and linguistically relevant problem gambling services, call the Massachusetts Problem Gambling Helpline (800-327-5050) or visit the Boston Chinatown Neighborhood Center website.

1. Interviews were conducted with members of the Khmer, Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese immigrant communities in the Greater Boston area.

Apr 20, 2023 | RESEARCH

Read the original article on The Basis HERE.

By Taylor Lee

“All you’ve got to do is stay away from gambling.” A woman described her experience with the stigma and blame of gambling problems by saying, “They look at it as being a weak person that is a problem gambler, someone that’s got no control over what they’re doing.” Shame and self-blame are common among people experiencing problem gambling, and they might intensify gambling problems by making it harder for people to regulate their emotions adaptively. This week, The WAGER reviews a study by Ana Estévez and colleagues that examined the relationship between shame and blame and problem gambling severity, as well as how emotion regulation mediates that relationship.

What was the research question?

How do shame and blame relate to problem gambling severity, and how does emotion regulation mediate that relationship?

What did the researchers do?

The authors surveyed 158 adolescents and young adults (119 males and 39 females of ages 12-30) from Northern Spain. Participants were divided into a non-clinical at-risk gambler group, a non-clinical problem gambling group, and a clinical problem gambler group based on their scores on the Spanish language version of the South Oaks Gambling Screen-Revised Adolescents scale. The researchers recruited the non-clinical samples from schools and the clinical sample from a treatment center. The researchers measure positive and negative moods, gambling motives, and emotion regulation. Next, they used Pearson’s r to assess the relationship between problem gambling severity, blame and shame, emotion regulation strategies for coping with negative life events, and gambling motives. Finally, the authors conducted a mediation analysis to examine the role of emotion regulation as a potential mediator in the relationship between problem gambling severity, and blame and shame.

What did they find?

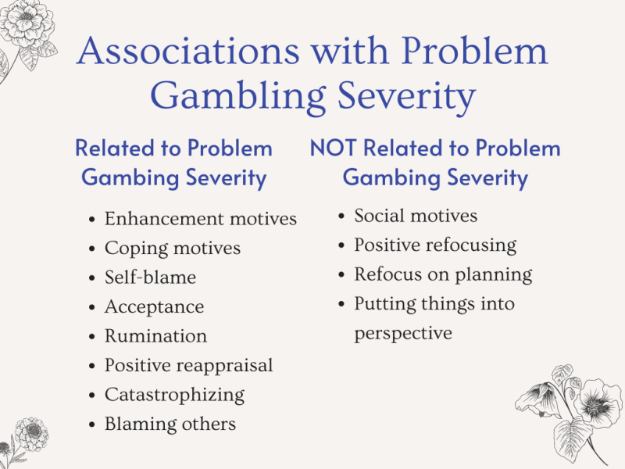

Participants with more severe problem gambling reported feeling more shame and blame. Additionally, they were more likely to report that they gambled to enhance their moods and cope with stress (but not to socialize) and to use several strategies to cope with negative life events: self-blame, acceptance, rumination, positive reappraisal, and catastrophizing. Three strategies for coping with negative life events–positive refocusing, putting things into perspective, and re-focusing on planning–were unrelated to problem gambling severity, and blaming others was negatively related to problem gambling severity. Finally, in the mediation analyses, using self-blame to cope with negative life events partially accounted for the relationship between problem gambling severity and shame at present and during the past 2 weeks.

Figure. Key points from Estévez et al. (2022) about the relationship between blame, shame, emotion regulation, gambling motives, and problem gambling severity, showing variables that were statistically significantly related to problem gambling severity.

Why do these findings matter?

Findings from studies such as this one can help inform evidence-based approaches to treatment and prevention. For example, learning that emotion regulation strategies like rumination and catastrophizing are related to problem gambling severity will allow for better-informed interventions such as dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), that teach healthier coping skills. Additionally, this study highlights the importance of conducting research on problem gambling in different contexts than the U.S., which speaks to the generalizability of predictors in other geographic locations, as (speaking very generally) blame is more prevalent in Western cultures, while shame is more dominant in Eastern cultures.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations of this study?

This study had a small sample size, so the results might not be generalizable across Spain or other countries, such as the United States. Furthermore, because socio-cultural factors were not recorded, it is unclear whether they had an impact on the role of blame and shame. The results are also likely not representative of populations in other countries and cultures where blame and shame may have different prevalence levels. Additionally, this is a cross-sectional study, so causal relationships cannot be determined.

For more information:

Do you think you or someone you know has a gambling problem? Visit the National Council on Problem Gambling for screening tools and resources. For individuals in Spain, visit this article for information on the Problem Gambling helpline.

Page 6 of 11« First«...45678...»Last »