Aug 7, 2024 | PROFESSIONALS, RESEARCH

Read the original article on The BASIS Here.

By John Slabczynski

Despite rising popularity, gambling remains a risky behavior that costs the U.S. an estimated $14 billion annually. One reason these costs are so high is because of the pervasiveness of gambling harms. Like other addictive behaviors, harms from gambling can stretch across multiple domains including social, occupational, health, financial, and even criminal. To minimize gambling harms, it is necessary to identify gamblers who might benefit from self-help tools or professional support, ideally before they experience severe consequences. One available screening tool is the Gambling Harms Scale 10 (GHS-10). One potential weakness of the GHS-10 is that it asks respondents to report whether they’re experiencing each harm using a simple “yes or no” format, rather than allowing them to report on how severely they’re experiencing a given harm. A person’s score is simply the total number of harms they’re experiencing. This week, The WAGER reviews a study by Philip Newall and colleagues that explored the validity of this measure by studying the lived experiences of gamblers in Australia with different levels of problem gambling severity according to the GHS-10.

What was the research question?

Is the GHS-10 a valid gambling harm screener, in that the lived experiences of gamblers relate in a logical way to their scores on the GHS-10?

What did the researchers do?

The researchers re-contacted a sample of 30 individuals from a previous study. These participants were recruited based on problem gambling severity according to scores on the GHS-10 from the previous study. Additionally, all participants were age 18 or older and had reported gambling within the past year. The research team then conducted semi-structured interviews with participants to elicit information about the role that gambling has played in their lives, including positive and negative experiences and harms to themselves and society more generally. The researchers grouped participants according to their GHS-10 scores (no-harm = 0 harms, low-harm = 1-2 harms, moderate-harm = 3-5 harms, and high-harm = 6-10 harms). Then they explored whether those with higher scores described having more severe negative experiences with gambling. This would support the idea that the GHS-10 is a valid measure.

What did they find?

Qualitative perceptions of gambling and experiences of harms were strongly related to participants’ GHS-10 scores (Figure shows themes and selected responses). For example, participants in the no-harm category described gambling as similar to any other leisure activity, with one participant describing the financial impact as the same as “collecting stamps”. In support of the GHS-10’s validity, as GHS-10 scores increased, so too did the propensity for financial harms. At the low-harm level, financial impacts were within reason but could veer towards regrettable. Participants in the moderate harm category occasionally experienced severe financial harms and participants in the high-harm category described significant financial harms. Interestingly, many other themes were present at multiple levels of problem gambling severity (e.g., gambling to build relationships) albeit with some adverse consequences or risk as problem gambling severity increased.

Figure: Displays the subthemes identified by the research team at each level of problem gambling severity, according to the GHS-10. A selected quote is shown under each subtheme that represents one participant’s understanding of each subtheme.

Why do these findings matter?

These findings are important because they provide more evidence for the utility of gambling harm screens, and the GHS-10 in particular. Specifically, this study showed that even without inquiring about the severity of gambling problems, the GHS-10 is able to discriminate between severe and less severe cases. Researchers should consider using this type of mixed methods approach that includes both quantitative and qualitative elements when studying gambling, as it can provide a more holistic view to better understand lived experiences.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

The researchers note that their background as gambling addiction researchers (and beyond that the developers of the GHS-10) might have biased their interpretations of participants’ qualitative responses. Additionally, though the overall sample contained 30 participants, no group of participants (i.e., across the no-harm, low-harm, moderate-harm, and high-harm gamblers groups) included more than eight participants, limiting the generalizability of this study.

Jun 17, 2024 | RESEARCH

Read the original article on The BASIS Here.

By Annette Siu

Professional adult athletes in Europe are more likely to gamble and are at an increased risk of problem gambling compared to non-athletes. This is potentially due to significant social and financial interrelations between sports and gambling. However, there is less known about gambling among younger athletes in Europe. It is especially important to address gambling within this age group because gambling at a young age is associated with an elevated risk of problem gambling and poorer mental health outcomes. This week, The WAGER reviews a study by Maria Vinberg and colleagues that examined the prevalence of problem gambling among young athletes at different skill levels in Sweden.

What were the research questions?

(1) Does the prevalence of problem gambling differ between male and female athletes who compete at different skill levels of their sports in Sweden?, and (2) Among young athletes, how do risky drinking and social acceptance of gambling relate to problem gambling?

What did the researchers do?

The authors recruited 1,636 athletes from the National Sports Education Program (“NIU” in Swedish) and 816 grassroots athletes, all aged 16 – 20 years old, to participate in this study. NIU athletes practice sports in connection with school and compete at an elite level, while grassroots athletes practice sports outside of school and compete at a non-elite level. To measure problem gambling and risky alcohol consumption, participants completed the Problem Gambling Severity Index and the AUDIT-C, respectively. The researchers also created a questionnaire to measure how accepting participants’ friends and family members were about gambling (e.g., “Gambling is important to my family”, “My classmates talk about gambling”).

What did they find?

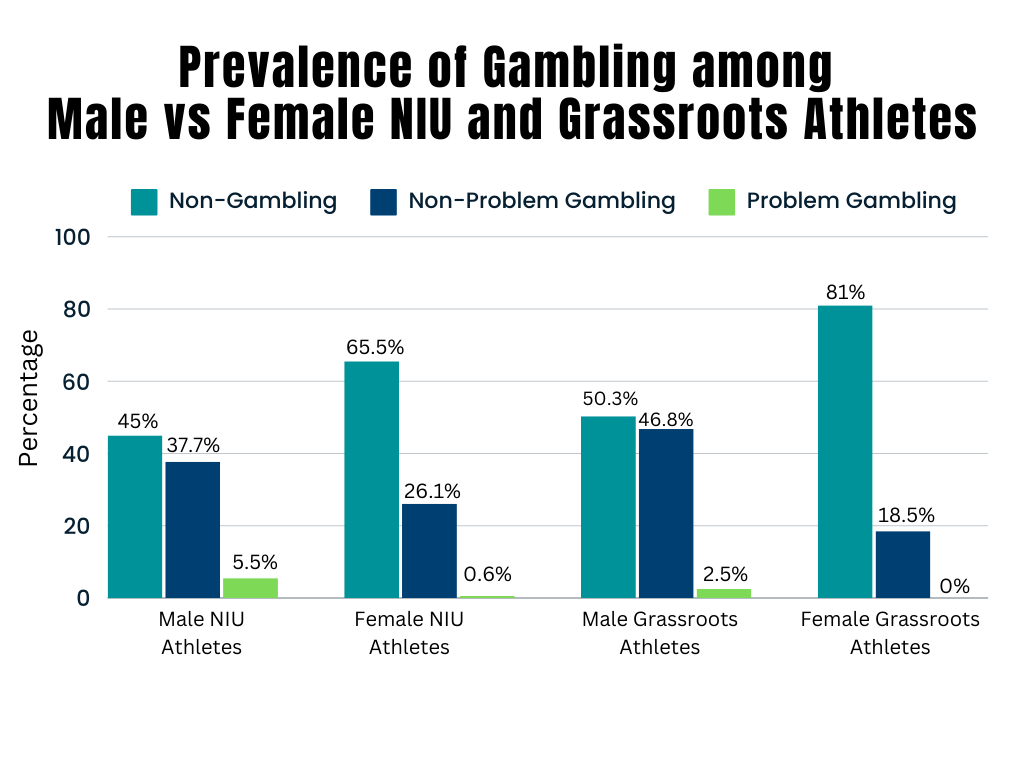

The prevalence of problem gambling was higher among males compared to females for both groups of athletes (see Figure). The prevalence was also higher among male NIU athletes (5.5%) compared to male grassroots athletes (2.5%). While problem gambling among female athletes was very low, female NIU athletes were more likely to gamble in a non-problematic way than female grassroots athletes (26.1% vs. 18.5%).

Additionally, risky alcohol consumption was associated with problem gambling among both groups, especially among NIU athletes. Among NIU athletes, those who reported risky drinking had more than twice the odds of problem gambling than those who did not report risky drinking. Problem gambling was also associated with several aspects of gambling acceptance, including having classmates who talked about gambling and having family/friends who viewed gambling as important.

Figure. Prevalence of gambling and problem gambling among male and female NIU (i.e., elite) and grassroots (i.e., non-elite) athletes.

Why do these findings matter?

Gambling is prevalent among young athletes in Sweden, particularly among elite male athletes. This study suggests that they are especially vulnerable to developing problem gambling if they have family, teammates, or coaches with positive attitudes towards gambling. Thus, it is important to educate young athletes about the risks of gambling and to create targeted resources that address various contextual factors (e.g., school and team environments) that affect them. The NCAA’s sports wagering e-learning module and substance misuse prevention program are two examples of this type of education program.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

This study was conducted in Sweden and only included athletes from a few selected sports (including ice hockey, football, floorball, golf, and cross-country skiing), so the results might not be generalizable to other countries with different gambling attitudes or to athletes from different sports. Additionally, the researchers only used self-report measures, so the responses might be impacted by social desirability bias.

May 22, 2024 | RESEARCH

Inside an academic building at the University of Memphis, there’s a suite with a bank of slot machines and distinct casino carpeting. To the uninitiated, it seems every bit like a casino. But upon closer exam, it’s actually a gambling “lab,” a place where gambling behavior is studied and analyzed.

The lab is one of several ways that the Tennessee Institute for Gambling Education and Research (TIGER) conducts a wide range of gambling research. Along with other research approaches, such as community surveys and crowdsourcing (through the internet, social media and smartphone apps), TIGER research covers a wide range of topics, including:

• Addictive disorders

• Examining and mitigating health disparities in urban and rural communities

• Assessment, prevention and treatment

• Psychotherapy process and outcome research

• Validation of assessment tools

• Understanding the relations between gambling, substance use and other comorbid conditions

The research emphasizes real-world application. “We believe in reciprocity between the experimental approach and the clinical approach,” says James Whelan, Ph.D., professor and executive director of TIGER, which consists of two arms: a gambling clinic that provides treatment to people with gambling problems and a gambling lab where research takes place. “What we learn in the lab setting informs what we do in the clinical space. And many of our research questions originate from experiences with people.”

The clinic keeps a database of the approximately 1,800 people they’ve treated and can ask questions of the database that include factors such as a client’s risk factors and demographics. “It always comes back to our experiences learning from people with lived experiences,” says Dr. Whelan. “Our goal is to generate knowledge that we can apply to improve outcomes.”

TIGER was established in 1999 after Dr. Whelan had a client whose depression was caused by gambling. “I realized that nobody really knew how to approach treatment for someone with a gambling problem and that this was likely to be an increasing need in the community as casinos were built,” says Dr. Whelan. From that initial experience, TIGER has grown to become a national and international leader in addressing gambling disorders and in contributing to literature for prevention and assessment and treatment.

After 25 years of gambling research, what findings have been the most surprising? Dr. Whelan mentions two areas. One involves the effect of substance use on gambling. “We figured the effect of alcohol would mean taking greater risks and stupid gambling,” he says. “But we actually found that it’s the gambling experience itself that creates risky drinking behavior. It’s as much a psychological issue as it is a physiological one. Until someone has a blood alcohol level of close to .09 and over, it doesn’t seem to have any effect on risk-taking decisions.”

Another finding that Dr. Whelan found interesting was the impact of cognitive-based interventions coupled with at least one visit to Gamblers Anonymous (GA). “Our research demonstrated that those going to a single GA meeting along with cognitive treatment had better outcomes than those who didn’t attend any meetings.” Dr. Whelan surmises that the importance of seeing others who have the same issue — even just once — plays a key role.

As gambling addiction research continues to spread in various directions — a period that Dr. Whelan refers to as “the wild west” — there is much to be excited about at TIGER. Some areas under study include how to maximize the impact of peer recovery specialists and how responsible gambling messages should be tailored to individual demographics, including those engaging in ever-growing sports betting.

“One of our studies focuses on younger men and the type of messaging that’s appropriate for them,” says Dr. Whelan. “We’re finding that they won’t use the terms “therapy” or “help” but they might ask for a “class” they can attend to help with a gambling problem.”

Another study on young men focuses on the relationship between gambling and college success. TIGER research finds that the more they gamble, the more likely they are to drop classes, which threatens to jeopardize the money they’ve invested in college.

Looking ahead, Dr. Whelan says that the gambling field is at an interesting juncture with great opportunity. “There needs to be cooperation and shared responsibilities between gambling operators and regulators that’s guided by research,” he says. “And there has to be a healthy respect for individual responsibility.”

The Tennessee Institute for Gambling Education and Research (TIGER) is funded by the Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services. For more information, visit https://www.memphis.edu/gamblingclinic/.

May 17, 2024 | PROFESSIONALS, RESEARCH

Read the original article on The BASIS Here.

By John Slabczynski

Due to the recent proliferation of new investing applications , more laypeople are engaging in retail stock market trading. Though some people have profited from this activity, many others have experienced significant harms. For example, in one high profile case, a young retail trader died by suicide because he (mistakenly) believed he suffered a huge trading loss. Several interested parties have also raised concerns around the gamification of the stock market, especially in brokerage apps like Robinhood, combined with the rapid pace of today’s retail trading, which calls to mind casino gambling. To prevent harm, it is important to understand specific mechanisms driving harms from investing. Therefore, this week, The WAGER reviews a study by Leonardo Weiss-Cohen and colleagues that examined how problem gambling severity and market volatility influenced trading intensity.

What were the research questions?

(1) Does problem gambling severity relate to trading intensity? (2) Does volatility in the market affect trading intensity?

What did the researchers do?

The research team invited 604 participants from an online survey panel to complete a simulated trading task. All reported both gambling in the past year and having lifetime experience buying a financial asset like a stock or bond. The researchers formed four semi-equally sized groups based on their scores on the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI); 1) recreational/no-risk gamblers, 2) low-risk gamblers, 3) medium-risk gamblers, and finally, 4) high-risk gamblers. In the trading task, each participant received a startup fund and had the opportunity to invest in six fictitious stocks on a computerized trading platform. Participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions, one with high volatility (i.e., stock prices moving up and down frequently) and one with low volatility. The research team manipulated the stocks in both conditions so that they would both have the same overall return (i.e., potential profit), albeit with significantly more volatility in the high volatility condition. To better replicate real-world behavior, participants received financial bonuses based on the results of their trading, with better performance resulting in higher bonuses. The researchers studied how problem gambling severity related to the intensity with which participants made stock trades, and whether participants traded more intensely when faced with high market volatility.

What did they find?

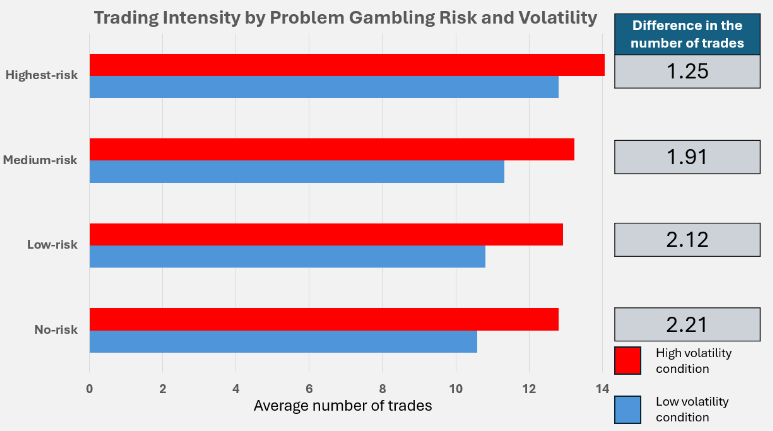

Contrary with other research, participants with more severe problem gambling did not trade more intensely. However, volatility did shape trading intensity; participants in the high volatility condition made 17% more trades compared to participants in the low volatility condition. This effect remained regardless of problem gambling severity and while controlling for financial literacy, overconfidence, age, and gender. Interestingly, exploratory analyses suggested that problem gambling severity may play a moderating role in predicting trading frequency, but only outside the highest levels of risk. Specifically, in all four of the gambling groups, participants in the high volatility condition traded more intensely than those in the low volatility condition; however, this difference was especially apparent in the three lowest-risk groups (see Figure).

Figure. Displays the mean number of trades for each PGSI category between conditions from exploratory analyses. The boxes on the right represent the average difference between participants in the high volatility vs. low volatility conditions for each level of PGSI severity.

Why do these findings matter?

These findings are important for two reasons. Namely, they suggest that volatile assets such as cryptocurrencies or high-risk stocks (e.g., penny stocks) encourage more intense, gambling-like trading than less volatile assets mutual or index funds. This suggests that the gamification of brokerage apps like Robinhood and Webull may be putting more users at risk than was initially expected. Additionally, because the effects of volatility were strongest among no-risk participants, messaging efforts should potentially target lower-risk traders and gamblers as well. Often, outreach messaging focuses on those most at-risk in the population, yet this study suggests that those at lower-risk might actually be experiencing more harms from trading.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

This study occurred in a simulated environment in which participants did not trade with their own personal money, so the external validity of this study is in question. Additionally, compared to the average online brokerage account, this study provided relatively modest amounts of capital to trade with. It is quite likely that higher stakes with more money could influence the results of this study, possibly by encouraging more risky trading.

For more information:

Individuals who are struggling with problem gambling may find support through Gamblers Anonymous. They offer in-person and virtual meetings. Others who are concerned about their trading or gambling behavior may benefit from visiting the website for The National Council for Problem Gambling. Additional resources can be found at the BASIS Addiction Resources page.

—John Slabczynski

Apr 18, 2024 | RESEARCH, SPORTS BETTING, YOUTH GAMBLING

Read the original article on The BASIS Here.

Written by: Kiran Chokshi

Editor’s note: This month’s WAGER was written by Kiran Chokshi, a high school senior from New York who’s interested in research about sports betting.

Many of us participated in team sports when we were younger, and some still play. Gambling has become increasingly present in sports in recent years as a result of the U.S. Supreme Court’s May 2018 decision, which expanded sports betting in the U.S. Researchers have begun to examine gambling behaviors among athletes themselves, and an open question is whether adolescent team sport participation might make one more likely to gamble later in life as a young adult. This week, The WAGER reviews a study by Brendan Duggan and Gretta Mohan which examined the associations between young people’s gambling behaviors and participation in team sports.

What were the research questions?

(1) Does exposure to a team sports environment in late adolescence lead to a greater likelihood of engagement in gambling as a young adult? (2) Are there gender differences in this relationship?

What did the researchers do?

The researchers collected data from Growing Up in Ireland (GUI), a longitudinal study with 2 waves of data for 5,190 participants born in 1998. Participants were asked in both waves (at age 17 or 18 in 2015 – 2016, and at age 20 in 2018 – 2019) if they participated in team sports, and also if and how often they participated in gambling activities online or in person. Participants who reported gambling once a month or more were considered to be regular gamblers.

What did they find?

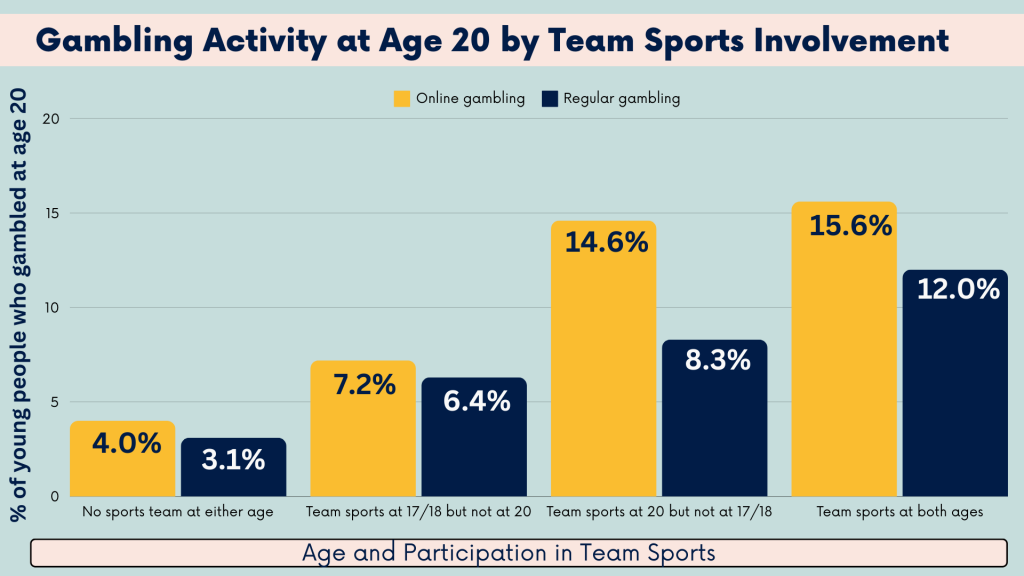

The researchers found that about one-third of participants took part in team sports, and males were more likely than females to play team sports and gamble at both waves. For both males and females, team sport participation significantly predicted future gambling engagement, both in terms of online gambling and regular gambling behavior. Participants who took part in team sports at both ages 17/18 and at age 20 had 2.44 higher odds of engaging in online gambling and 2.99 higher odds of being a regular gambler at age 20, when compared to participants who did not engage in team sports at either wave. When looking at the sample of males only, these relationships were stronger; males who participated in team sports at both waves had 3.8 higher odds of online gambling and 4.02 higher odds of gambling regularly, when compared to males who did not play team sports in both waves.

Figure. Figure shows the percentage of participants engaging in online or regular gambling based on their participation in team sports. Total N = 5,190. Adapted from Duggan & Mohan (2022).

Why do these findings matter?

Many professional sports teams and leagues are embracing betting and collaborating with sportsbooks, with some going so far as to sign sponsorship deals. Although gambling is prohibited to some extent among athletes at most levels of competition, problem gambling is a potential risk among amateur and professional athletes. The results from this study highlight how adolescent team sport participation predicts future online and land-based gambling, which could potentially lead to Gambling Disorder. Interestingly, many prevention groups, such as the New York State Office of Addiction Services and Supports, recommend participation in team sports, clubs, and community groups as a positive outlet; however, this research suggests that kids who are playing sports might benefit from targeted public health programs about problem gambling. Future research should test the effectiveness of these prevention programs among amateur and elite athletes alike.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

Although the sample size in this study was large, all of the participants were from Ireland, so it’s unclear if these findings are generalizable to people in other countries with different gambling practices. The data in this study was also self-reported, so might under- or over-report actual gambling behaviors. A more specific limitation of the study is that it did not track the amount of gambling spending per person, so the authors were unable to determine how much money each participant spent or lost while gambling.

For more information:

If you or anyone you know has a gambling problem, visit the National Council on Problem Gambling for tools and resources to help. Resources for preventing underage gambling are also accessible through YouthDecide. For additional resources, including gambling and self-help tools, visit our Addiction Resources page.

— Kiran Chokshi

Mar 20, 2024 | RESEARCH

Read the original article on The BASIS Here.

Written by: Annette Siu

Gambling harm is a significant issue among culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) community members who live in disadvantaged areas in Australia. This problem is exacerbated by the fact that gambling harm assessment options require gamblers to self-disclose to healthcare providers, as CALD community members are less likely to discuss gambling with their providers due to stigma and language barriers. One potential solution is to implement screening for gambling-related problems in primary and community care settings, which could help improve access to Gambling Disorder treatment for CALD community members. This week, The WAGER reviews a study by Andrew Reid and colleagues that examined enablers of and barriers to a pilot study that implemented a gambling harm screening model in primary and community care settings.

What was the research question?

What are some enablers of and barriers to implementing a gambling harm screening model for CALD community members in primary and community care settings?

What did the researchers do?

The researchers implemented a problem gambling screening and referral model in general practice and community-based services in Fairfield, Australia, an area with a large CALD population. The screening model included the Problem Gambling Severity Index short form and the Concerned Others Gambling Screen. If the client screened positive for being at-risk for gambling harm on either measure, the provider would give them a list of gambling help resources for them to read and contact.

Following implementation, the researchers conducted interviews with two general practitioners and seven community workers who administered the screening model with 130 patients. The goal was to learn about factors that facilitated and hindered the implementation of the screening model.

What did they find?

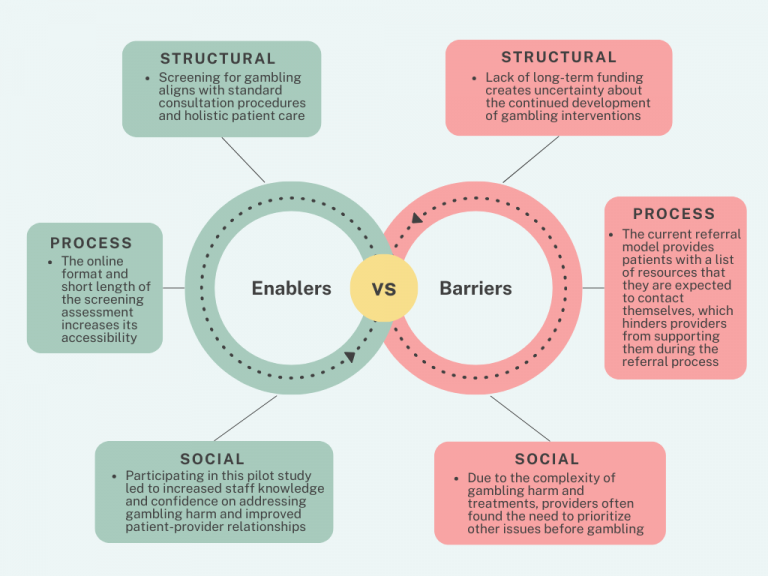

One structural factor that facilitated implementation was alignment with standard consultation procedures (see Figure for key enablers and barriers). Participants indicated that it was easy to integrate the screening model, as it supported their existing holistic patient care approaches. Process-related factors that facilitated implementation included the screening assessment’s online format and short length, which made it easier to administer and increased its accessibility to patients. One social factor that facilitated implementation was increased staff knowledge and empowerment. Participants explained that taking part in the pilot project increased their confidence in discussing gambling with patients and addressing gambling harm.

One structural factor that hindered implementation was a lack of long-term funding, which created uncertainty about the continued development and expansion of gambling interventions (see Figure). One process-related factor that hindered implementation was an unclear referral model. The model only provided patients with a list of resources for them to contact themselves, so providers were not able to adequately support their patients through this process. Finally, a social factor that hindered implementation was the complexity of gambling harm, as some patients seemed to be in greater need of other services, such as mental health and financial services, compared to gambling help services.

Figure. An overview of key enablers and barriers to the implementation of the gambling harm screening and referral model.

Why do these findings matter?

Integrating problem gambling screening in primary healthcare and community service settings can help to support holistic patient care procedures, increase access to gambling support services, and mitigate gambling harm within communities. Primary care providers who are involved in discussing gambling with their patients can also play a role in reducing stigma related to gambling issues and help-seeking by using person-first, humanizing language. The current study highlights the importance of not only increasing access to gambling harm screening, but also providing support and referring patients to appropriate gambling help resources.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

One limitation is that the researchers only interviewed nine participants who were general practitioners and community workers; they did not interview other people such as practice nurses and practice owners who were also involved in implementing the screening model. Additionally, to better evaluate the effectiveness of the problem gambling screening model, future research should examine the model’s acceptability from the perspective of community members from different cultural backgrounds.

For more information:

Individuals who are concerned about their gambling behaviors or who simply want to know more about problem gambling may benefit from visiting the National Council on Problem Gambling or Gamblers Anonymous. Additional resources can be found at the BASIS Addiction Resources page.

— Annette Siu

Page 4 of 10« First«...23456...10...»Last »