Jan 8, 2026 | RESEARCH

Read the original article on The BASIS here.

By John Slabczynski

Like other addictive behaviors, gambling disorder is linked with risk for suicidality. This is particularly alarming during an era of gambling expansion. To save lives, public health advocates need to understand this relationship. For example, to what extent does gambling disorder increase the risk for suicidality when co-occurring conditions, such as depression and anxiety, are accounted for? This week, The WAGER reviews a study by Adonay Kidane and colleagues that explored the relationships among gambling disorder, suicidality, and co-occurring conditions.

What was the research question?

How do gambling disorder and other mental health issues relate to suicidality within a large nationally representative sample?

What did the researchers do?

The researchers used two nationally representative Swedish datasets, the National Patient Register (NPR) and the Cause of Death Register (CDR). The NPR includes records of mental health disorder diagnoses, suicide attempts, and more. The researchers used it to identify 3,594 patients diagnosed with gambling disorder between 2005-2019. Using a case-control design, they selected two age- and gender-matched patients from the dataset without gambling disorder, resulting in 10,782 total participants. The researchers then merged in CDR data on completed suicides. Through logistic regression, they explored how gambling disorder and other mental health diagnoses relate to suicidality, which was defined as the presence of either a suicide attempt or completed suicide.

What did they find?

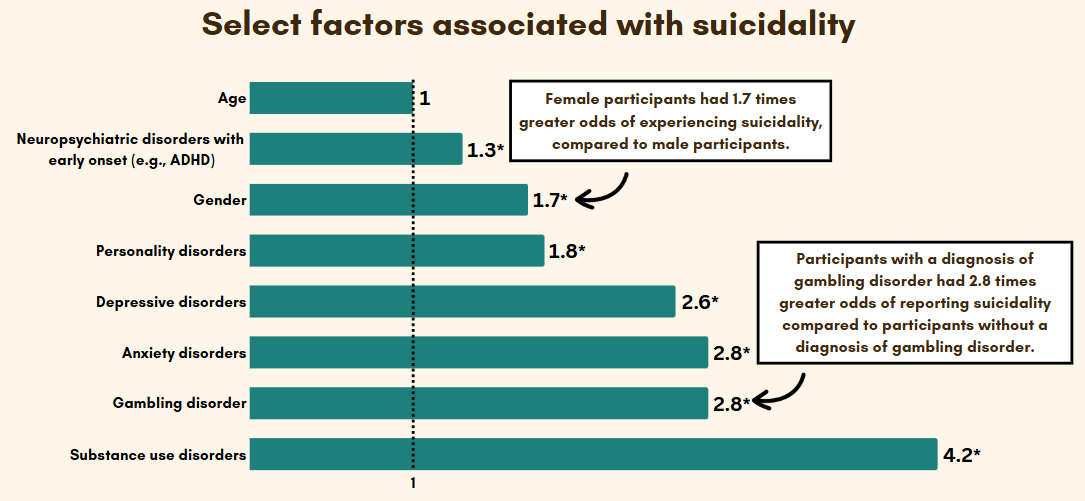

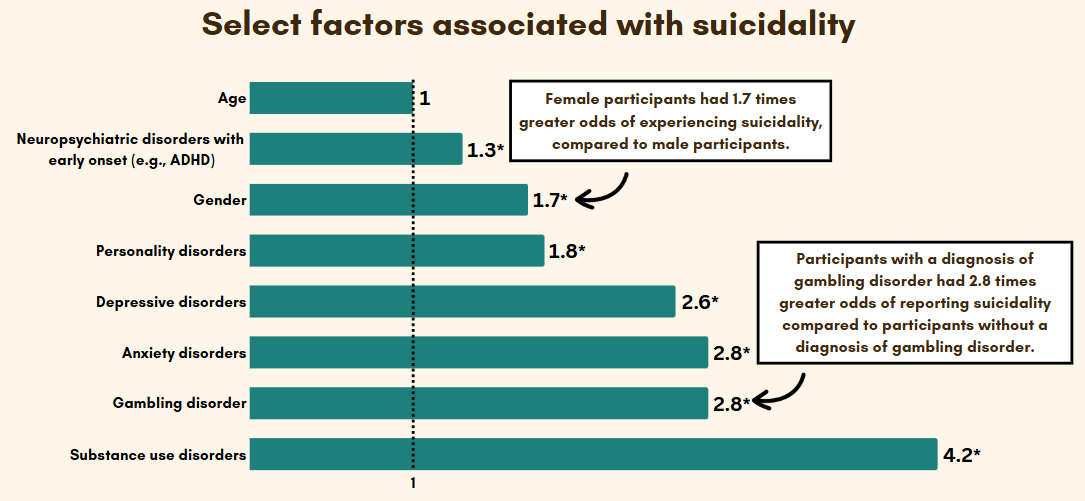

Participants diagnosed with gambling disorder (17.7%) had 2.8 greater odds of suicidality compared to matched controls (1.6%) (see Figure), controlling for demographics and comorbid mental health diagnoses. In this model, substance use disorders had the highest risk increase for suicidality (see Figure).

Figure. Displays the odds of suicidality as a function of several potential risk factors among the total sample (N = 10,782). Odds ratios can be interpreted as having X times higher odds of reporting an outcome. * denotes a statistically significant relationship.

Why do these findings matter?

These findings indicate that gambling disorder is associated with increased risk for suicidality even when the researchers accounted for other conditions that might independently create risk for suicide. This underscores the need for routine suicide risk-assessment and safety planning among those experiencing gambling disorder.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

This study was a secondary analysis of existing datasets, so it is limited by how the original data were collected. The NPR, for example, only identifies cases for which a formal diagnosis was made. Most people with gambling disorder do not seek help, so those who do get formally diagnosed might have more severe cases compared to the general population.

For more information:

Individuals who are concerned about their gambling may benefit from engaging with Gamblers Anonymous. Others who are concerned that they may hurt themself may benefit from visiting the CDC webpage on suicide prevention. Additional resources can be found at the BASIS Addiction Resources page.

—John Slabczynski

Dec 17, 2025 | RESEARCH, RESOURCES

The National Council on Problem Gambling (NCPG) has released new findings from its National Survey on Gambling Attitudes and Gambling Experiences (NGAGE 3.0), offering an updated picture of how Americans are gambling—and what they believe about gambling.

The first NGAGE survey was conducted in 2018, just as states began legalizing sports betting following a landmark Supreme Court decision that opened the door for rapid expansion across the country. A follow-up survey in 2021 revealed a sharp increase in risky gambling behavior. At the time, researchers weren’t sure whether the spike reflected the spread of sports betting or the stress and isolation from the COVID-19 pandemic.

The 2024 survey, conducted after pandemic restrictions had largely lifted, shows that gambling-related risks have stabilized. About 8% of U.S. adults—nearly 20 million people—reported experiencing at least one sign of potentially problematic gambling “many times” in the past year. That number is down from 11% in 2021 but still higher than the 7% reported before sports betting became widely available.

“While it’s reassuring that the increases in problematic gambling behavior we saw in the 2021 survey seem to have abated along with the easing of the COVID-19 pandemic, maladaptive gambling remains a significant public health problem,” says Don Feeney, who helped design the NGAGE surveys. “Increased efforts at prevention and education are essential if we are to reduce gambling-related harm.”

The survey also sheds light on who is most at risk. Younger adults, men, online gamblers and sports bettors were among the groups most likely to report signs of risky play. Those who gamble frequently or participate in many different gambling activities are especially vulnerable.

“The best predictors of a gambling problem aren’t participation in any particular form of gambling,” explains Don. “Instead, the best predictors are the intensity of gambling involvement—how frequently someone is gambling—and the breadth of involvement—how many different forms of gambling someone is involved with.”

Even as legalized sports betting has expanded to 39 states, Washington, D.C. and Puerto Rico, the overall share of Americans placing sports bets has remained steady at about 23%. However, the ways people are betting are changing. The number of sports bettors making parlay bets—wagers that combine multiple outcomes for the chance of a large payout—has nearly doubled since 2018. Researchers note that these types of bets can be especially appealing to those trying to “win back” losses quickly, a pattern often associated with risky play.

Another key finding involves public attitudes toward gambling addiction. While nearly three in four adults agree that gambling addiction is similar to drug or alcohol addiction, fewer than 40% consider its consequences “very severe.” Many still believe gambling problems stem from a lack of willpower or moral weakness rather than recognizing them as treatable health conditions.

There is, however, some encouraging progress. Awareness of problem gambling helplines has increased, and most people understand that helplines exist to help people struggling with gambling problems.

“We’ve learned that we can improve awareness that there’s help for a gambling problem, and that awareness is greatest among those most in need of receiving services,” says Don. “However, these are the same people who are most skeptical that treatment works. We need to make the effectiveness of treatment an integral part of our message.”

Despite the progress, challenges remain. Public funding for problem gambling services has increased—from about $80 million in 2018 to $134 million in 2023—but seven states still provide no funding at all. On average, states spend just 35 cents per resident on prevention, education and treatment programs.

Continued investment and public awareness are critical to preventing gambling-related harm. Prevention and education work, but more people need to understand that help works too—and that recovery from gambling problems is possible.

The survey underscores that even as gambling becomes more common, many people still misunderstand the risks. Open discussion about gambling addiction, promoting the effectiveness of treatment and making help easy to find is necessary to keep gambling a form of entertainment rather than a source of harm.

Nov 7, 2025 | RESEARCH

Read the Original Article on The Basis HERE.

By Nakita Sconsoni, MSW

Psychiatric comorbidity, such as substance use and mental health disorders, is common among those with problem gambling. It is also common among sexual minority populations (i.e., LGBTQ+), in part, due to the higher rates of discrimination and violence that they may experience compared to their heterosexual and cisgender counterparts. According to minority stress theory, these factors might contribute to poor mental health and the development of addictive behaviors, potentially including problem gambling. This week, The WAGER reviews a study by Magaly Brodeur and colleagues that examined gambling tendencies and explored factors associated with problematic gambling among LGBTQ+ individuals.

What were the research questions?

(1) How do LGBTQ+ individuals gamble and (2) what factors are associated with problematic gambling among this population?

What did the researchers do?

The researchers developed an online panel of 1,519 LGBTQ+1 identifying adults, using stratified random sampling to ensure the sample was representative of the Canadian population. Participants completed an online survey that measured sociodemographic characteristics, such as age and ethnicity, past-year gambling habits, problem gambling severity, and mental health. Participants were separated into two problem gambling score categories: no-to-low-risk gambling and problematic (i.e., moderate to high risk) gambling. The researchers used a multivariate logistic regression analysis to determine factors associated with problematic gambling.

What did they find?

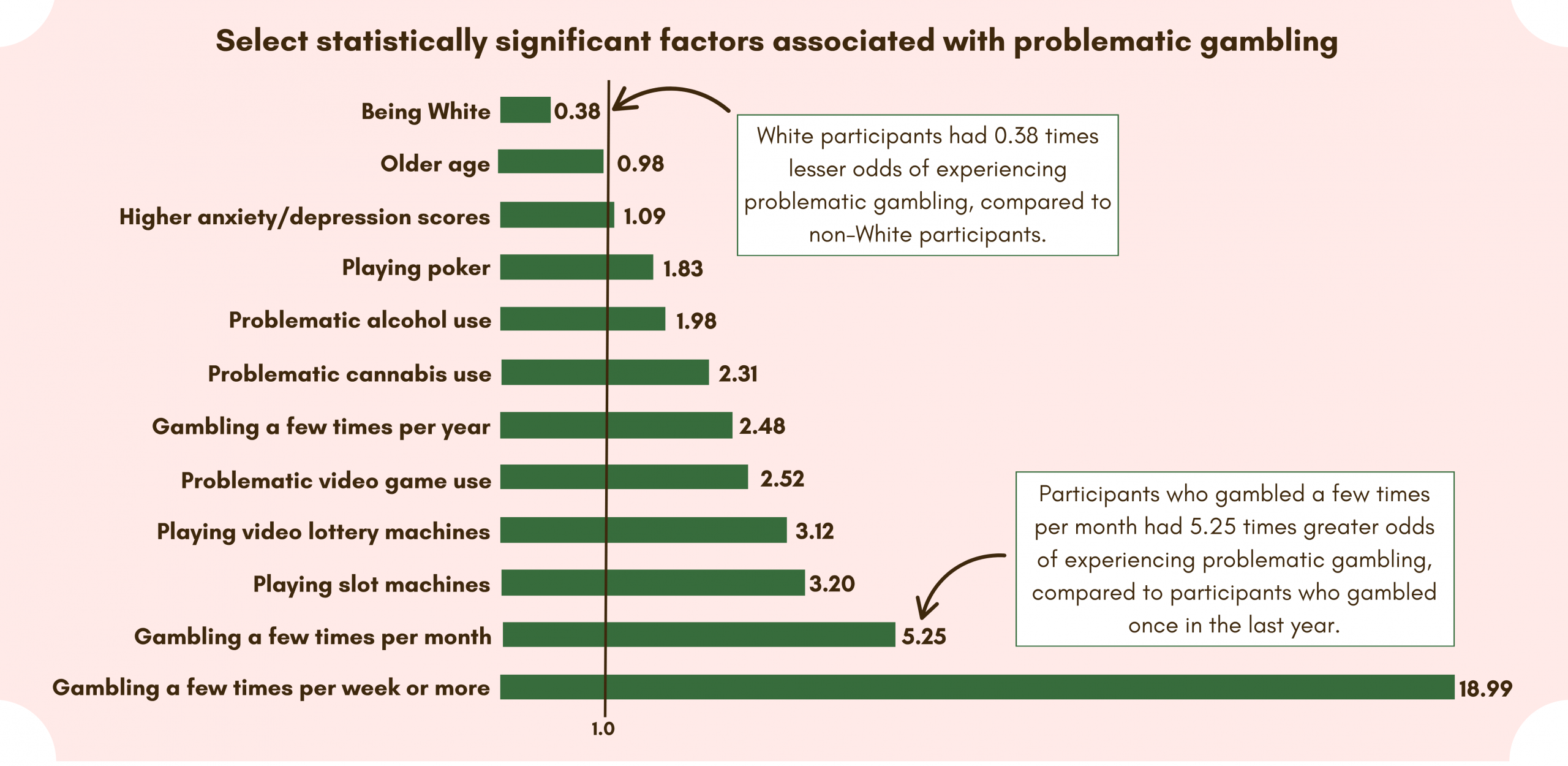

The most common forms of gambling among the entire sample were lottery tickets (75%) and scratch tickets (68%). Among those exhibiting problematic gambling, poker (53%) and video lottery machines (51%) were most prominent. Approximately one-fifth (19.6%) of participants exhibited problematic gambling. The logistic regression model identified factors associated with lower odds of experiencing problematic gambling, such as being older and White, and higher odds of experiencing problematic gambling, such as gambling more frequently, engaging in problematic substance use, engaging in certain types of gambling, and experiencing higher rates of depression/anxiety (see Figure).

Figure. Displays the odds ratios of select factors associated with problematic gambling among LGBTQ+ participants that were found to be statistically significant. Click image to enlarge.

Why do the findings matter?

The findings indicate that problematic substance use and poor mental health, along with gambling patterns, are associated with problem gambling symptoms among LGBTQ+ individuals. In doing so, they support the role of minority stress in problematic gambling. Connecting clients to community support organizations like Boston GLASS might help relieve minority stress while providing resources and offering opportunities to engage in activities that do not involve gambling. Additionally, providers should apply an intersectional lens to understand how other marginalized identities, such as non-White race, may influence a person’s vulnerability to addictive behaviors, like gambling.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

This study was cross-sectional, which means we cannot conclude that the identified factors caused problematic gambling. Additionally, the sample sizes for some of the subgroups was small, which might make prevalence estimates inflated or unstable, so those particular results should be interpreted with caution. Finally, qualitative studies could provide a deeper understanding of the role that identity and minority stress play in the LGBTQ+ population’s relationship with gambling.

1. More specifically, the researchers surveyed LGBTQIA2S+ individuals. This acronym stands for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer/Questioning, Intersex, Asexual, 2-Spirit, and other gender identities/sexual orientations not explicitly listed.

Sep 5, 2025 | PROBLEM GAMBLING, RESEARCH

Two newly published reports, commissioned by GambleAware and developed in collaboration with IFF Research, have highlighted a concerning connection between neurodivergence and gambling harms. Conducted by Dr. Amy Sweet of the University of Bristol and Dr. Tim Morris of University College London and the University of Bristol, the studies indicate that neurodivergent individuals—those with conditions such as ADHD, autism, dyslexia, dyspraxia or dyscalculia—are more vulnerable to experiencing gambling-related harm, despite not gambling more frequently than neurotypical individuals.

The first report explored the availability and effectiveness of support for neurodivergent gamblers. It found that individuals with conditions like autism or ADHD often struggle with impulsivity and financial management, which can intensify the risks associated with gambling. For many, gambling becomes a “coping mechanism,” offering temporary relief from feelings of social isolation, marginalization or unmet mental stimulation needs. However, these strategies often lead to serious consequences, including financial hardship, damaged relationships and setbacks in education or employment.

The report emphasized the need for tailored treatment approaches that consider specific traits like attention difficulties. Early intervention is crucial, as many individuals only seek help after facing significant harm. The study also called for streamlined, accessible support services and greater use of peer networks to offer non-judgmental spaces for those hesitant to engage with formal treatment systems.

The second report pointed to a significant knowledge gap in the understanding of how gambling affects neurodivergent people. It noted that the intersection of gambling harm and neurodiversity remains under-researched, and encouraged further studies to explore how factors such as age, gender and ethnicity may influence these experiences. This lack of data presents both a challenge and an opportunity to improve future prevention and support strategies.

In response to the findings, Haroon Chowdry, GambleAware’s director of evidence and insights, stressed the need for improved public awareness around gambling risks, including mandatory health warnings and clearer support pathways. Clare Palmer of IFF Research added that their next phase will involve developing practical tools in partnership with Ara Recovery 4 All and lived experience experts to enhance future service delivery.

Overall, the reports underscore the urgent need for more inclusive, responsive gambling support systems tailored to the unique challenges faced by neurodivergent individuals.

Sep 4, 2025 | RESEARCH

Read the Original Article on The Basis HERE.

By Matthew Tom, Ph.D.

Drug use disorders, pathological gambling, compulsive shopping, and other similar mental health problems were once thought of as separate and disconnected phenomena. According to the Syndrome Model of Addiction, advanced by Dr. Howard Shaffer and colleagues, risk factors for addiction – whether chemical and behavioral – include common themes and life circumstances. Researchers are continuing to look for these “primary causes” and mechanisms that can cut across different expressions of addiction. This week, as part of our Special Series in Honor of Dr. Howard Shaffer, The WAGER reviews a study by Sophie G. Coelho and colleagues that examined the perceived causes of several different expressions of addiction.

What was the research question?

From the perspective of people with lived experience, are the perceived causes of addiction similar across different forms of addiction?

What did the researchers do?

The researchers used data from the Quinte Longitudinal Study of Gambling and Problem Gambling. This prospective survey solicited people 18 years or older living within 70 miles of Belleville, Ontario, Canada, from 2006 to 2011. The 4,122 participants were a 74%/26% mix of people recruited randomly and a group overly selected for higher levels of gambling. A total of 1,473 participants reported problematic substance abuse, gambling, or other behavior. The researchers asked participants which behaviors led to “significant negative consequences” (e.g., financial difficulties, relationship issues). For each mentioned behavior, the researchers asked, “What was the main cause of [your problem with the substance/behavior]?” Participants’ responses were open-ended text, and the researchers used content analysis to classify responses. They classified participants’ types of addiction into three categories (substance use versus gambling versus other behavioral addictions), and then counted how many participants in each class gave each main cause. They used a chi-square test to determine if there was a difference in the three classes’ distributions of main causes.

What did they find?

Out of 25 main causes the researchers gleaned from the participants’ responses, 10 were common to all three classes. The most common cause was coping (see Figure), either with other mental health issues like depression, physical ailments such as nausea, or other life stressors such as family problems. Other main causes common to the three classes of addiction include enhancement (e.g., gambling for excitement), poor self-control, and the addictive properties of the substances or activities themselves. Main causes that were unique to certain classes included [chemical] withdrawal (specific to substance use disorders), money and trying to “win” (specific to gambling), and hunger (specific to eating, as another behavioral addiction). The researchers did find differences in the distributions of main causes. For example, participants were more likely to mention inherently addictive properties as a main cause of their addiction when discussing substance use disorders (e.g., “Tobacco is highly addictive”), while enhancement and excitement were more common in gambling and in other behavioral addictions.

Figure. Six of the eight most common main causes of addictive behavior and the categories of addictive behavior they led to. The two of the eight not shown are “Unclear” and “Unsure of cause.” Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

Understanding the etiology of addiction is important, even if certain causes are more common for particular addictions than they are for others. For instance, researchers and clinicians can explore whether combining treatment seekers into support groups by main causes, rather than by current problems, might yield better treatment outcomes faster. To illustrate, people who all started engaging in addictive behaviors as a way of coping with depression and loneliness might be able to empathize with each other, even if some have problems with alcohol while others have problems with gambling. Treatment providers might find ways to think beyond the common practice of promoting services for one specific type of addiction, and find themselves able to serve much wider client bases than they originally envisioned.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations of this study?

The participant pool resided completely within a single province in Canada, so the results might not be generalizable to other populations. The researchers grouped the different types of addiction into three broad classes, combining drugs with very different properties into one class, the many different forms of gambling into another, and a wide range of behavioral addictions into a third. Grouping participants or types of addiction this way might have kept the researchers from pinpointing specific main causes unique to specific substances, gambling games, or behaviors.

Aug 13, 2025 | RESEARCH

Read the Original Article on The Basis HERE.

By John Slabczynski

Gambling policy in the U.S. is driven by a combination of federal, state, and municipal regulations. This patchwork approach allows for the spread of relatively unregulated gambling opportunities, particularly online. These unregulated online operators often present unique risks to consumers, such as deposit insecurity—as evident during ‘Black Friday’, the 2011 federal shutdown of major online poker sites. As the U.S. moves towards a safer and more regulated market, it is important to understand how such regulation influences the consumer experience. This week, The WAGER reviews a study by Kahlil Philander and Bradley Wimmer that explored how online poker players value government regulation.

What was the research question?

How much are online poker players willing to pay for government-regulated online poker?

What did the researchers do?

The researchers recruited 783 U.S. and Canadian online poker players (21 years and older) from poker-related websites and on social media. The participants completed a discrete choice experiment (DCE)1. Each participant was presented with two hypothetical online poker sites that varied on five features (see Figure), and were asked to choose the operator they preferred. Participants completed this task eight times, with a different combination of opposing operator features each time. They also indicated their attitudes and beliefs towards government regulation. The researchers estimated the dollar value participants were willing to pay for government-regulated poker gambling and whether this differed based on a player’s preferred stake size.

What did they find?

On average, online poker players were willing to pay an additional $1.83/hour to play on government-regulated sites, though this varied based on factors like a player’s preferred stake size. For example, at micro-stakes,2 participants were willing to pay an average of $0.88 compared to $5.35 at middle-stakes. Furthermore, attitudes appear to be an important factor in a consumer’s price point insofar as those who held negative attitudes towards government regulation were less willing to pay more for government regulation, and at times even willing to pay more to play on an unregulated site. For example, those who played at either micro-stakes or small-stakes and believed that government regulation would lead to increased taxation showed an aversion to sites that offer such regulation.

Figure. Displays the five features involved in the DCE. The left-most column lists the specific features and the middle-left column describes each feature. The columns on the right show examples of two hypothetical online poker sites with opposing features (Option A and Option B). During the experiment, participants selected the operator who appealed more to them based on their differing features. Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

The findings from this study suggest that government-regulated poker sites are generally more appealing to online poker players compared to sites without such regulation, and so regulation might be important for the future health of the poker industry. However, it is also important to note that this study was conducted before recent changes to U.S. federal gambling regulations. For example, bettors can no longer deduct all of their gambling losses from their taxes. With fears of taxation a primary detractor to the value of government regulation, it is unclear how this legislation might affect the perceived value of government regulated gambling going forward.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

This study focused on online poker players and thus may not be generalizable to the wider population of people who gamble. Notably, previous studies suggest that poker players may differ from other gambling populations on a number of factors. This study was also unable to acquire a representative sample (i.e., higher stakes bettors comprising an outsized proportion of the sample) that might have biased the results.

________________

1. The researchers conducted two prior qualitative studies to inform the development of the final DCE.

2. For micro-stakes games, the big blind can be as high as $0.50. Small-stakes big blinds are between $0.50 and $2.00 and middle-stakes big blinds are between $2.00 and $10.00.

Page 1 of 1112345...10...»Last »