NGAGE 2.0 and the 2021 MN State Lottery, Gambling Participation Rates of Minnesota Adults.

Presenting the most recent national and Minnesota data regarding gambling attitudes and experiences.: READ MORE

Where to Draw the Line

THE WAGER: Gamblers’ difficulty in estimating their gambling outcomes

Read the original article on The Basis website HERE

By John Slabczynski

Many responsible gambling strategies, such as setting a budget, rely on bettors to monitor their own gambling behavior. However, monitoring one’s own gambling has key limitations, as gamblers often underestimate their losses or overestimate their wins. These problems with recall might be due to the complexity of calculating gambling outcomes and the particular phrasing of gambling expenditure questions. This week, The WAGER reviews a study by Robert Heirene and colleagues that examined the accuracy of self-reported gambling outcomes (as compared to actual betting records) when participants were informed of specific ways to calculate these metrics.

What was the research question?

How accurately do participants report their gambling outcomes when given instructions on how to calculate them? Additionally, what variables predict estimation inaccuracy?

What did the researchers do?

The researchers recruited 652 customers1 from an online gambling operator via email and asked them to complete a short questionnaire. The questionnaire asked participants to estimate their total number of bets placed in the past 30 days and net gambling outcome, defined as total winnings or losses during this same period. Unlike prior studies that also assessed the accuracy of gambling expenditure, these researchers provided instructions on how to calculate these metrics. The researchers then compared participants’ reported number of bets and outcomes to their actual behaviors which were provided by the online gambling operator in the form of electronic betting records. Finally, the researchers assessed whether certain variables predicted the accuracy of estimated gambling outcomes.

What did they find?

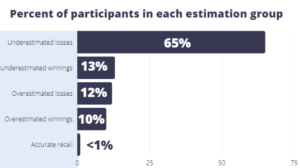

Only 7.4% of participants estimated their betting frequency within a 10% margin of error of their actual betting frequency, with 69.6% underestimating their betting frequency. Estimates of net gambling outcomes were similarly biased; only 4.1% reported a gambling outcome within a 10% margin of error, and 64.8% underestimated their losses (see Figure). Participants’ actual net gambling outcome was the greatest predictor of estimation inaccuracy, particularly among those with a net loss. Underestimating winnings was the second most common estimation error, yet only 12.8% of participants made this error.

Figure. Percentage of participants in each estimation error group based on the difference between their self-reported net outcome and actual net outcome (i.e., based on electronic gambling record data). Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

These findings show that even when given specific instructions on how to calculate their net gambling outcome, participants still failed to accurately estimate winnings or losses. This brings into question the effectiveness of many responsible gambling strategies, as people might not be able to consistently recognize when they’ve passed their betting limits. It may be better to have gambling operators provide bettors with frequent updates on their real gambling expenditure. This study also highlights potential validity issues in other gambling studies that rely on self-report.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

First, this article only assessed participants’ involvement on one online gambling operator and thus did not capture activity on other sites. Second, a very small number of participants (i.e., 1.9%) who received the recruitment email participated, and those who did participate appeared to have different gambling habits compared to those who did not participate.

For more information:

The Responsible Gambling Council has tips to gamble more responsibly. If you are worried about you or someone you love’s gambling habits, you can find gambling support resources at The National Council on Problem Gambling. Additional resources can be found at the BASIS Addiction Resources page.

— John Slabczynski

Gamban

Working your recovery program is hard. To help assist those who may feel tempted to gamble online or visit a casino or card room, there are a few tools that may be helpful. None are foolproof, but if you are committed to your recovery, these tools may help.

GAMBAN – a voluntary, self-exclusion tool for online gambling sites.

Given that many gamblers may be moving online, especially during COVID-19 times, MNAPG is offering individual subscriptions for an online self-exclusion tool called Gamban. This tool enables the gambler to block tens of thousands of online gambling sites on all devices. MNAPG has purchased one-year subscriptions that can block up to 15 devices in one household. If you are interested, please email sstucker@mnapg.org and a link will be provided to set up the account.

Status of Telehealth Counseling Uncertain

Minnesota’s Department of Human Services continues to follow the federal health emergency guidelines for providing telehealth services. The current three-month approval will end in November. As of mid-October, there was no indication from DHS — one way or the other — as to whether this will continue.

Given the success of telehealth counseling and Minnesota’s expansive geography and often-hazardous winter weather, MNAPG will continue to advocate for this service becoming a permanent tool for counselors and therapists. With only 18 certified problem gambling providers in the state of Minnesota, most located in the Twin Cities metro area, we believe telehealth counseling is an essential tool in helping those experiencing harm from gambling, whether a gambler or a family member. While in-person will always be the gold standard, we think the accessibility of telehealth counseling can be extremely helpful for those seeking to begin their recovery.